Art born of isolation

Solitude can be difficult, but art serves to remind us that we are not alone in whatever we are feeling

Art born of isolation

As lockdown continues in the UK, as the weeks begin to roll into months, it can seem as though everything has been put on pause, that our lives have become smaller and less exciting. But there are some unexpected upsides to our confinement. Friends are talking more than they did before and neighbours are cooking, shopping and looking out for each other. And with nowhere to go, no reason to travel, people are also discovering the worlds on their doorsteps, the chirruping wonders in their back gardens and the blossoming trees of local parks.

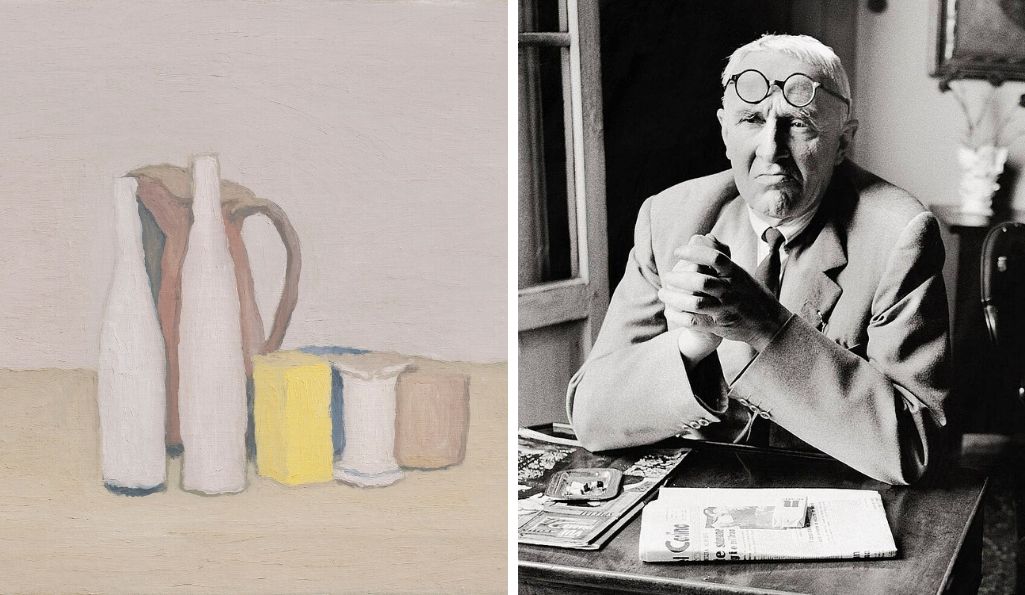

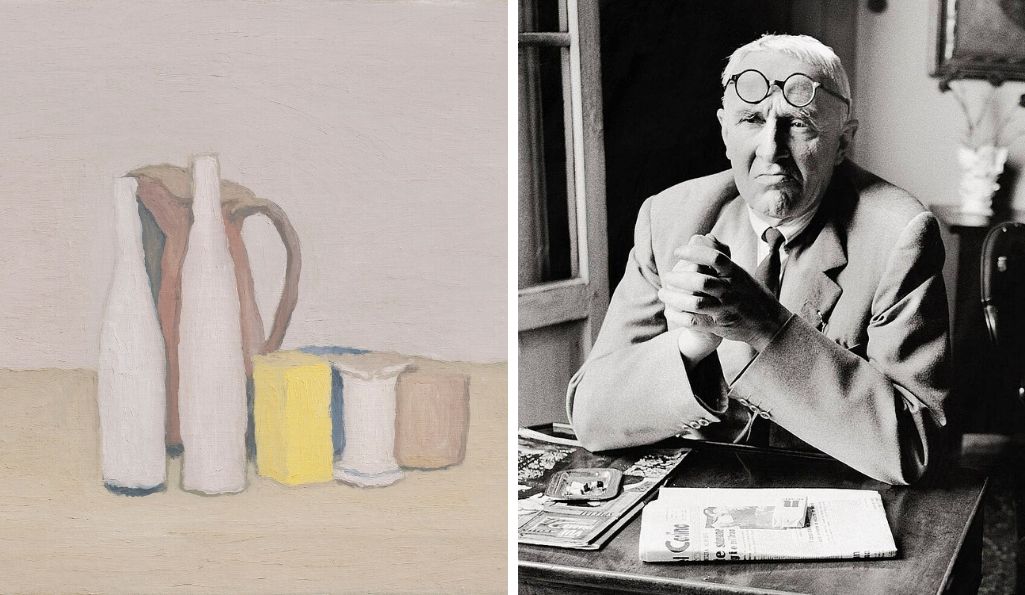

Our isolation has forced most of us to slow down and notice the details. And this is a huge part of what art does, too. It helps us see what is right in front of our eyes, to appreciate simplicity. Giorgio Morandi (b1890) was an artist who forged a successful career doing just this, even as all around him turned to chaos. Morandi was born and raised in Bologna, where he lived his entire life with his three sisters. Even as the second world war disrupted the world around him, his paintings focussed on more enduring states of being, on the calm of a simple arrangement of vases, on pale shadows falling on white porcelain. By concentrating on form and colour and subtle variations in tone, Morandi lends noble weight to modest domestic items. Ceramic bottles take on elegant personalities and squat little pots seem to guard towering jugs.

Left: Giorgio Morandi. Natura Morta (1952). Right: Giorgio Morandi

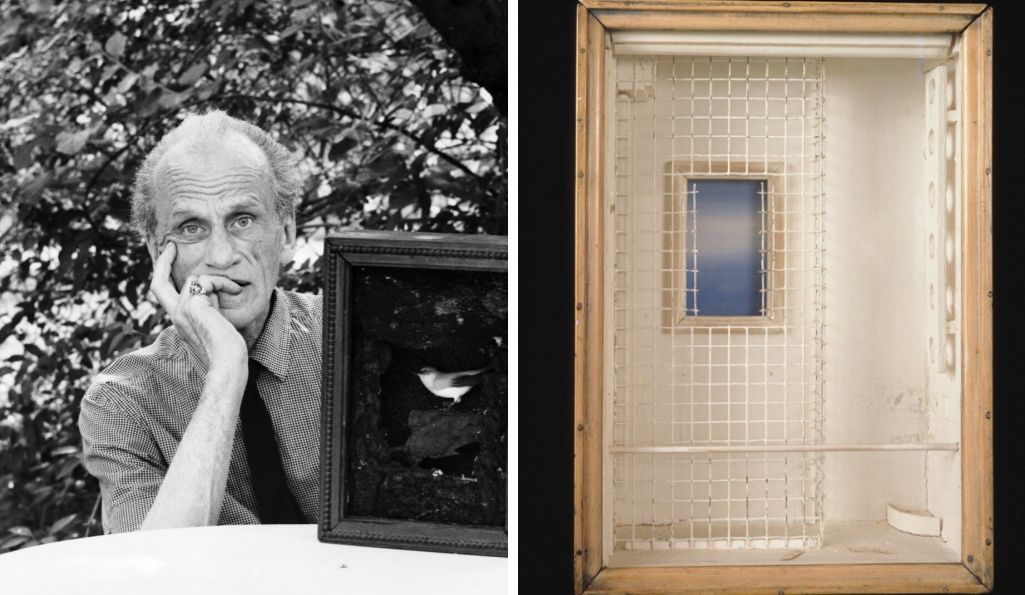

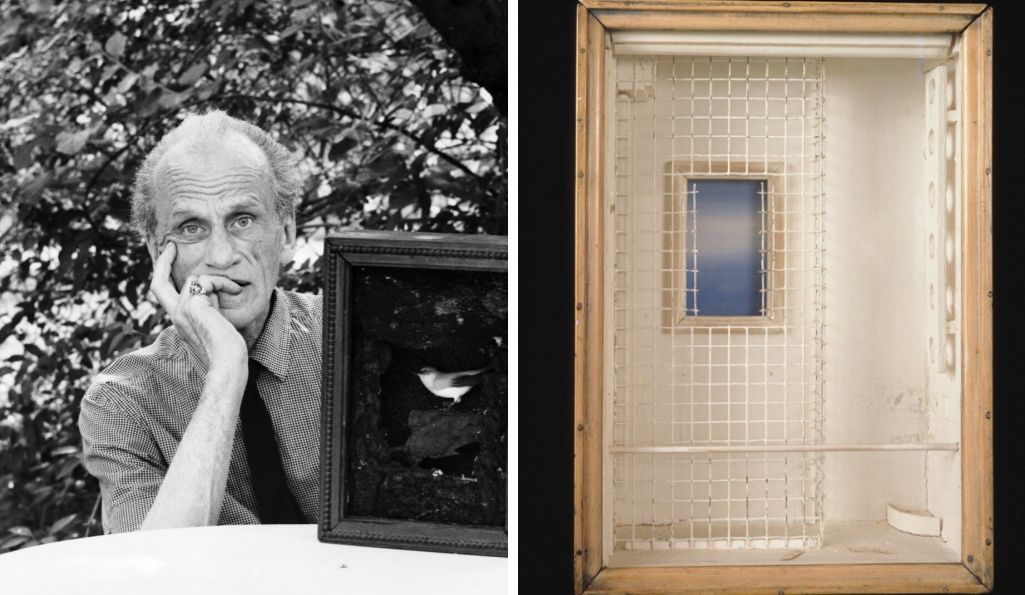

As Morandi was exposing the hidden significance of simple forms, another artist working at the same time was also conjuring up fresh perspectives from the everyday. Joseph Cornell (b1903) never travelled abroad and barely left his native New York, where he lived in the basement of a house he shared with his mother and disabled brother. But he was a successful artist with an imagination that knew no bounds. With the paper ephemera he collected in bric-a-brac stores and bookshops he was able to construct surreal environments befitting a Jules Verne novel. In this way Cornell travelled an imaginary world influenced by exotic plants and animals, by European theatres and maps of the heavens. He juxtaposed these found illustrations with objects, such as shells, marbles, bells and beads, to form small dioramas that hinted at much larger realms .

'The poet Emily Dickenson was famously reclusive, and Cornell – who was himself a shy man – sympathised and perhaps even identified with her isolation.'

While many of Cornell’s assemblages were filled with colourful decoupage images of parrots and illustrations from encyclopaedias, he also made quieter works. Toward the Blue Peninsula: For Emily Dickenson is one such piece. The poet Emily Dickenson was famously reclusive, and Cornell – who was himself a shy man – sympathised and perhaps even identified with her isolation, her ‘tortuous seclusion,’ as he put it. His homage to this kindred spirit takes the form of a small aviary, painted white (Dickenson developed a penchant for white clothing), with a little window that looks out to the blue skies beyond. The cage is empty, as the bird has escaped through a hole cut in the wire. Through the power of art, she has been set free.

Left: Joseph Cornell. Right: Joseph Cornell. Toward the Blue Peninsula: For Emily Dickenson (1953)

Even those of us who are not naturally shy and retiring can need seclusion, to ‘get away from it all,' at times of trauma and uncertainty. And this is precisely what Georgia O’Keeffe (b1887) did. For O’Keeffe, the New Mexico desert offered respite, especially after a breakdown that saw her hospitalised for three months. She described the northern regions of the state as 'such a beautiful, untouched, lonely feeling place, such a fine part of what I call the faraway.’

'O'Keeffe described the northern regions of New Mexico as 'such a beautiful, untouched, lonely feeling place, such a fine part of what I call the faraway.''

For 40 years she made annual trips to the 21,000-acre Ghost Ranch in northern New Mexico, where she stayed for months at a time in a modest adobe house. From there she could explore the surrounding dessert and paint the seductive shapes she found in rock formations and animal bones. The features of this landscape gave her huge amounts of satisfaction and she loved one mountain above all others, saying, ‘it’s my private mountain. It belongs to me. God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it.’

Unlike Morandi and Cornell, O’Keeffe travelled widely, exploring Europe and the Middle East, and when she was in New Mexico she did receive visitors. But she liked the seclusion of her desert haven and loved the place so much, that when she died in 1986 aged 98, her ashes were scattered on the land around Ghost Ranch.

Left: Georgia O'Keeffe, Cow's Skull with Calico Roses (1931). Right: Georgia O'Keeffe.

Being an artist is often a lonely pursuit at the best of times, requiring hours of isolation in a studio. But through art we can all learn to see things we hadn't noticed before, to find escapism in faraway places and to seek solace in the making and the viewing. But more than that, art in every form is about shared experience, about realising that we are not alone in whatever we are going through. It is also about knowing that things will get better.

Our isolation has forced most of us to slow down and notice the details. And this is a huge part of what art does, too. It helps us see what is right in front of our eyes, to appreciate simplicity. Giorgio Morandi (b1890) was an artist who forged a successful career doing just this, even as all around him turned to chaos. Morandi was born and raised in Bologna, where he lived his entire life with his three sisters. Even as the second world war disrupted the world around him, his paintings focussed on more enduring states of being, on the calm of a simple arrangement of vases, on pale shadows falling on white porcelain. By concentrating on form and colour and subtle variations in tone, Morandi lends noble weight to modest domestic items. Ceramic bottles take on elegant personalities and squat little pots seem to guard towering jugs.

Left: Giorgio Morandi. Natura Morta (1952). Right: Giorgio Morandi

As Morandi was exposing the hidden significance of simple forms, another artist working at the same time was also conjuring up fresh perspectives from the everyday. Joseph Cornell (b1903) never travelled abroad and barely left his native New York, where he lived in the basement of a house he shared with his mother and disabled brother. But he was a successful artist with an imagination that knew no bounds. With the paper ephemera he collected in bric-a-brac stores and bookshops he was able to construct surreal environments befitting a Jules Verne novel. In this way Cornell travelled an imaginary world influenced by exotic plants and animals, by European theatres and maps of the heavens. He juxtaposed these found illustrations with objects, such as shells, marbles, bells and beads, to form small dioramas that hinted at much larger realms .

'The poet Emily Dickenson was famously reclusive, and Cornell – who was himself a shy man – sympathised and perhaps even identified with her isolation.'

While many of Cornell’s assemblages were filled with colourful decoupage images of parrots and illustrations from encyclopaedias, he also made quieter works. Toward the Blue Peninsula: For Emily Dickenson is one such piece. The poet Emily Dickenson was famously reclusive, and Cornell – who was himself a shy man – sympathised and perhaps even identified with her isolation, her ‘tortuous seclusion,’ as he put it. His homage to this kindred spirit takes the form of a small aviary, painted white (Dickenson developed a penchant for white clothing), with a little window that looks out to the blue skies beyond. The cage is empty, as the bird has escaped through a hole cut in the wire. Through the power of art, she has been set free.

Left: Joseph Cornell. Right: Joseph Cornell. Toward the Blue Peninsula: For Emily Dickenson (1953)

Even those of us who are not naturally shy and retiring can need seclusion, to ‘get away from it all,' at times of trauma and uncertainty. And this is precisely what Georgia O’Keeffe (b1887) did. For O’Keeffe, the New Mexico desert offered respite, especially after a breakdown that saw her hospitalised for three months. She described the northern regions of the state as 'such a beautiful, untouched, lonely feeling place, such a fine part of what I call the faraway.’

'O'Keeffe described the northern regions of New Mexico as 'such a beautiful, untouched, lonely feeling place, such a fine part of what I call the faraway.''

For 40 years she made annual trips to the 21,000-acre Ghost Ranch in northern New Mexico, where she stayed for months at a time in a modest adobe house. From there she could explore the surrounding dessert and paint the seductive shapes she found in rock formations and animal bones. The features of this landscape gave her huge amounts of satisfaction and she loved one mountain above all others, saying, ‘it’s my private mountain. It belongs to me. God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it.’

Unlike Morandi and Cornell, O’Keeffe travelled widely, exploring Europe and the Middle East, and when she was in New Mexico she did receive visitors. But she liked the seclusion of her desert haven and loved the place so much, that when she died in 1986 aged 98, her ashes were scattered on the land around Ghost Ranch.

Left: Georgia O'Keeffe, Cow's Skull with Calico Roses (1931). Right: Georgia O'Keeffe.

Being an artist is often a lonely pursuit at the best of times, requiring hours of isolation in a studio. But through art we can all learn to see things we hadn't noticed before, to find escapism in faraway places and to seek solace in the making and the viewing. But more than that, art in every form is about shared experience, about realising that we are not alone in whatever we are going through. It is also about knowing that things will get better.

TRY CULTURE WHISPER

Receive free tickets & insider tips to unlock the best of London — direct to your inbox