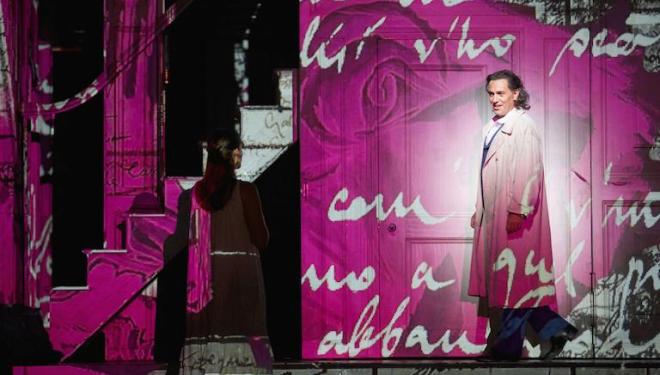

With its showstopping arias, dazzling ensemble pieces and twisting storyline, Don Giovanni is a power-packed night at the opera. Little wonder, then, that the Royal Opera House is reviving this spectacular production to launch its 2022/23 season.

In the title role is Italian baritone Luca Micheletti. His manservant Leporello is sung by British baritone Christopher Maltman.

Malin Byström (Donna Anna), comforted by Daniel Behle's Don Ottavio in Covent Garden's Don Giovanni in 2019. Photo: Mark Douet

There will be a lot of interest in the Royal Opera House of German-born conductor Christian Trinks, making his house debut, with a growing reputation for exciting work in the German repertoire.

Sir Antonio Pappano leaves the Royal Opera House as music director in 2024, when he takes over the London Symphony Orchestra from Sir Simon Rattle. Rattle is moving to Munich's Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, after the death last year of its conductor, Maris Janssons. As the great musical merry-go-round keeps turning, all eyes are on his likely successor.

Don Giovanni is sung in Italian with English surtitles. Performances are on 8, 13, 16, 19, 21 and 26 September

| What | Don Giovanni, Royal Opera House |

| Where | Royal Opera House, Bow Street, Covent Garden, London, WC2E 9DD | MAP |

| Nearest tube | Covent Garden (underground) |

| When |

05 Jul 21 – 18 Jul 21, Seven performances with one interval |

| Price | £9-£200 |

| Website | Click here for more information and booking |